Blue-billed Duck

Blue-billed DuckOxyura australis | |

|---|---|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Anseriformes |

| Family: | Anatidae |

| Sub-Family: | Oxyurinae |

| Status | |

| World: | Near threatened (IUCN 2021) |

| Australia: | Least concern |

| Victoria: | Vulnerable (FFG Threatened List 2023) |

| FFG: | Listed; Action Statement No. 174 |

The Blue-billed Duck (Oxyura australis) is a stiff-tailed diving duck. Its genus name Oxyura is derived from the Greek oxys -sharp and oura - tail. The adult male has a distinctive sky-blue bill, glossy black head and chestnut body plumage, which is most evident during the breeding season but may remain throughout the year.

Non-breeding plumage in males can vary and the bill can appear grey in partial eclipse or dark green in full eclipse plumage. Females are brownish-grey with pale barring and do not have plumage change. It can be difficult to distinguishing between males in full eclipse plumage, females and juveniles.

Non breeding male, female and immature Blue-billed Ducks can appear similar to the female Musk Duck, which is also a stiff-tailed diving duck. Distinguishing features include more rounded head of the Blue-billed Duck and a concave bill rather than the triangular bill of the Musk Duck. The Blue-billed Duck is noticeably smaller than the Musk Duck, males being about 60% shorter and females 30% shorter (Marchant & Higgins 1990, Simpson & Day 1999).

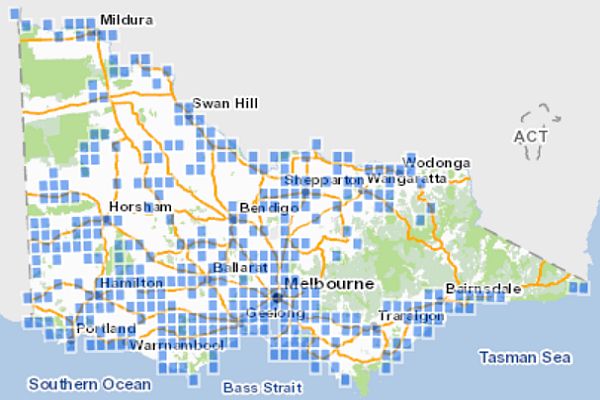

Distribution

The Blue-billed Duck occurs in Australia's temperate regions, in both southwest Western Australia and the eastern Australia. The highest concentrations in eastern Australia are in southern Victoria. The Australian population is estimated at 12,000 breeding birds (Environment Australia 2000), although the majority are found on artificial wetlands, for example the main site for this species in Victoria is the Melbourne Western Treatment Works at Werribee.

Regional overview of important wetlands.

Port Phillip

- Western Treatment Works at Werribee

- Devilbend Reservoir

South West Victoria

- Western district lakes Lake Terangpom, Lake Gnarpurt, Lake Rosine, Lough Calvert and Cundare Pool, Lake Corangamite (now unsuitable due to extremely high salinity >166,000 EC). Deep Lake, Lake Tooliorook, Lake Bookaar, Lake Colongulac, Lake Milangil, Lake Oundell, Lake Yallakar, Lake Purrumbete.

- Lake Linlithgow, Lake Bolac, Lake Turangmoroke, Lake Jollicum.

- Tower Hill, Kaladbro Swamp

- Condah wetlands and sections of the Glenelg River

- Lake Modewarre, Lake Murdeduke

- Lake Wendouree, Lake Buninjon

- Lakes in the Horsham area, Kurrayah Swamp, Dock Lake and Lake Witton Natimuk Lake, Lake Carchap near Natimuk.

North East Victoria

- Wahgunyah Sewerage Treatment Plant, Lake Kerford near Beechworth and the Winton Wetlands.

Gippsland

- Newmerella Sewage Farm

- Dowds Morass

North West Victoria

The Mallee CMA commissioned the Arthur Rylah Institute (ARI) to examine data on Blue-billed Ducks in the region, collected during annual Summer Waterfowl Counts between 1984 to 2008. Blue-billed Ducks were recorded at 49 wetlands within the study area. The study also found that numbers of Blue-billed ducks have declined in the period between 1984 and 2008 (Purdey & Loyn 2008).

The most important wetlands for Blue-billed Ducks with (mean average) in descending order were Lake Wandella (45), Irymple Tank (36.7), Wargan Channel east ponds (23.6), Wallpolla Creek (20), Round Lake (16.4) , Wargan Channel (10.6), Tutchewop (98), Koorlong Lake (96), Wargan Channel north-east (8.8), Benetook Swamp (7.5), Lake Elizabeth (6.4) and Cullens Lake (6.2).

The maximum count was 374 at Lake Wandella on 14 March 1992. All high counts were recorded in the 1980s and 1990s except for a count of 100 at Round Lake on 23 February 2000.

Round Lake and Lake Elizabeth may now be the only wetlands in the region to support regular large flocks of Blue-billed Duck (Purdey & Loyn 2008). Round Lake was closed to hunting in 2015 due to high numbers of Blue-billed Ducks (Purdey & Menkhorst 2015).

A study of Blue-billed Ducks in North West Victoria between 1984 and 2008 found that numbers were highest in years when Murray River tributary rivers at Quambatook, Wakool Junction and Loddon River, Kerang had high flow rates i.e. wet years (Purdey & Loyn 2008).

Note: this is not intended to be a complete list of every wetland that has a record of Blue-billed Ducks in Victoria but rather wetlands which have a high probability of occurrence provided conditions are suitable.

Ecology & Habitat

The Blue-billed Duck inhabits fresh to saline, deep permanent open wetlands and deep, densely vegetated lakes. During the breeding season (November - March) there is a tendency to disperse to deep freshwater wetlands that have abundant aquatic and emergent vegetation although many birds remain on large wetlands (Hewish 1988).

Types of habitat and vaules

In Victoria, Blue-billed ducks have been recorded from 207 waterbodies which can be categorised into the following; Dam (26 locations), Farm Dam (13 locations), Lake (74 locations), Sewerage Treatment Plant ponds (37 locations), Storm water treatment function (13 locations) and Wetland (44 locations) (Cull, Newman & Plew 2021).

Adapted from (Cull, Newman & Plew 2021)

Breeding Habitat

Widely distributed sites, smaller in nature with fewer Blue-billed Ducks residing, in numbers typically less than 10. These habitats have the highest value as they replenish the species and require an increased level of protection.

Loafing Habitat

Typically, high to very high numbers of Blue-billed Ducks on much higher water areas including on many artificial sewage treatment and settling ponds. There was no reported breeding on these sites which gives them a medium rating as they are not directly contributing to replenishment, or recruitment, of the species.

Drop-in type Habitat

Blue-billed Ducks infrequently observed and generally only for the day. These could be transit sites for migration or, perhaps more likely, have unfavourable characteristics such as pollution with little to no feeding, little aquatic vegetation, little fringing vegetation suitable for nesting, shallow and hence transient nature – disappearing in drought times. Some sites with prior ongoing habitation were seen to drop into this category suggesting habitat quality decline – due potentially to pollution, salinity, European Carp infestation (Purdey-Loyn, 2008), and increasing recreational use. This is the least value habitat type.

Use of habitats

Open water habitat

The minimum open water distance of a waterbody required for Blue-billed Ducks has been observed to be 97metres which allows birds to enter and exit the water. A study of nearly 16,000 observations and records between 2015 to 2021 across Victoria found no Blue-billed Ducks on smaller waterbodies, however the mean open water distance for small waterbodies the ducks use was found to be from 250m to 300m (Cull, Newman & Plew 2021).

Breeding habitat

Analysis of records and field observations by (Cull, Newman & Plew 2021) found a number of common habitat characteristics for Blue-billed Duck breeding:

- At least 140 metres of deep and open water with no possibility of overgrowth and not impeded by tall trees and other high vegetation.

- Significant visible aquatic vegetation such as Ribbon Weed, and benthic vegetation such as Eel Grass to support a wide range of invertebrates.

- Significant areas of fringing Bull Rush (Cumbungi) for nesting which verges the deep and open water.

- An absence of European Carp which cloud the water and damage or destroy Benthic vegetation, the turbidity reducing or stopping the growth or regeneration of the vegetation, reducing invertebrates (Purdey-Loyn, 2008).

Behaviour

Flocking

In winter, Blue-billed Ducks may congregate in large flocks on large clear lakes and more saline wetlands, preferring open water usually away from the shoreline. The level of movement is likely to be influenced by seasonal conditions such as rainfall, lake levels and water salinity.

Breeding

Breeding takes place from from Spring to late Summer. Suitable breeding sites may hold winter flocks, provided they contain dense marginal vegetation and large expanses of open water, which could explain why some males remain sedentary and retain full breeding plumage into winter. Nests are mostly solitary and constructed in spring on low trampled swamp vegetation such as rushes and sedges.

Ducklings stay under the care of the female duck for the first 4-5 weeks.

Feeding

The Blue-billed Duck feeds on variety of aquatic insect larvae, molluscs and aquatic plant material including leaves and seeds. They have a diving habit and stay underwater for up to 30 seconds per dive (Emison et al. 1987, Marchant & Higgins 1990).

Population status

Counts of waterbirds on Victoria's wetlands over five years (1988-1991) indicated the Blue-billed Duck population could be at least 1600 in Victoria (Peter 1991). A more recent analysis of 73 counts between the years 2000 - 2012 at the Western Treatment Plant wetlands at Werribee found an average of 4078 Blue-billed Ducks. In 2013 in excess of 10,000 Blue-billed ducks were recorded in this area (Loyn et al. 2014).

It has been noted that Blue-billed Ducks tend to congregate at the Western Treatment Plant wetlands in drought years when habitat across their range becomes unsuitable. They tend to disperse in years when other wetlands hold more suitable water levels.

The Victorian Summer Waterbird Counts demonstrate how the population count can vary. The 2011 Victorian Summer Waterbird Count only recorded 15 Blue-billed Ducks (Purdey and Loyn 2011). The 2012 Victorian Summer Waterbird Count recorded 845 Blue-billed Ducks; Port Phillip (793 mostly at the Western Treatment Plant), North East (8), North West (16), Gippsland (15), South West (13). The 24 year long-term average of Blue-billed Ducks in the Victorian Summer Waterbird Counts is 3779 (Purdey and Loyn 2013).

The 2014 and 2015 summer waterfowl counts found the Port Phillip Region (i.e. Western Treatment Plant) held most of the Blue-billed Ducks counted across Victoria (98.3% in 2014; 92.2% in 2015) (Purdey & Menkhorst 2015).

If the populations on artificial wetlands/treatment ponds were excluded a more accurate reflection of Blue-billed Duck status in natural habitats would emerge, where flocks in excess of 90 birds are uncommon and many wetlands support less than 10 birds.

Analysis of data by Cull, Newman & Plew 2021, indicates that whilst there may be a few years when the population can peak from 6000 to 8000 birds, being a very large number at one site, but for the majority of time the population in Victoria ranges from 2000 to 2500 birds.

In Victoria there are only 25 wetlands which have records of 100 or more Blue-billed Ducks. There were 17 known breeding sites in Victoria in 2008 (Purdey-Loyn, 2008). In 2021, (Cull, Newman & Plew 2021) conducted further analysis of databases finding 27 sites where breeding has occurred.

Threats

Loss of suitable wetland habitat

- drainage, salinisation, lowering of groundwater and lake levels.

- degradation to natural wetland vegetation (aquatic and emergent) and loss of suitable breeding habitat, i.e. European Carp, inappropriate grazing.

- increased salinity from runoff, erosion, low groundwater and drought conditions.

The high concentration of Blue-billed Ducks on areas such as the Melbourne Western Treatment Works at Werribee tends to disguise what has happened to populations on natural wetlands which have been impacted upon by reduced water levels and higher salinity levels in recent years.

Habitat decline

Changes to waterbodies in terms of use, disturbance and habitat degradation can influence the use of value of a waterbody for Blue-billed Ducks. For example, the presence of European Carp and/or lack of aquatic and fringing nesting vegetation can change the use from loafing habitat to occasional drop-in habitat or no habitat value at all.

Shallow waterbodies quickly overgrown by fringing, then other vegetation, below the required 100 metres of open, unenclosed water. It is no longer possible for the BBDs to access or leave, hence they are no longer visiting

Disturbance

Opening waterbodies to recreational activities can cause birds to disperse. The Blue-billed Duck is a shy bird, not liking close contact which discourages habitation and nesting. A frequently disturbed or aggravated female won’t nest and will seek more sheltered, private, secure habitat.

Previously significant loafing habitat which supported high numbers of Blue-billed Ducks were observed to dropped to zero or only occasional drop-ins which coincided with the opening of the reservoirs to recreational boating and fishing (Cull, Newman & Plew 2021).

Game management

The long term impacts from the now banned use of lead shot is unclear, but may pose an on-going problem in some waters which were subject to heavy hunting in the past. Lead poisoning is known to occur at a much higher incidence for diving ducks (Pain 1992).

The Blue-billed Duck is a protected species which must not be hunted (Game Management Authority). Impacts from hunting may have been a factor in the past, for example in 1987 it was recorded that 61% of Blue-billed Ducks counted on Victorian wetlands were on waters open to hunting and 2.1% of these ducks were illegally harvested, this equated to an estimated 1.3% of the entire pre-season count (Loyn 1987). As the number of viable wetlands has been reduced over the last 15 years or so due to low water levels the impact of hunting could be exacerbated as it is concentrated on fewer wetlands. This situation has been managed to some extent by altered duck hunting arrangements such as reduced hunting season and water closures. In addition, the level of illegal harvest has been minimised through improved hunter identification and licensing procedures.

Conservation & Management

The conservation status of Blue-billed Duck was re-assessed from Endangered in 2013 to Vulnerable in 2020 as part of the Conservation Status Assessment Project – Victoria (DELWP 2020). This species is now listed as Vulnerable in Victoria and under the Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988 - Threatened List - June 2021 (DELWP 2021).

Questions have been raised over the re-classification by Cull, Newman & Plew 2021, given an overall decline in habitat, development pressure on habitats, impacts from climate change, a very limited number of breeding sites and an ongoing reduction of observations across several years.

Suggested priorities by (Purdey & Loyn 2008).

- Maintain fringing vegetation as possible nesting sites.

- Maintain benthic vegetation to drive productivity of bottom layers where the species feeds.

- Maintain open water at a suitable depth (>1m).

- Avoid increases in salinity beyond a certain level (~5000 mg/l).

- Exclude European Carp.

Other management & research

- Protect aggregations of Blue-billed Ducks from disturbance and accidental shooting, by temporary closure of wetlands (or parts of the wetlands) using the provisions in the Wildlife Act 1975.

- Characterise breeding seasons, habitat and nest requirements from directed studies of breeding biology.

- Determine land status and security of breeding and non-breeding sites and potential threats or impacts to these sites.

- Conduct surveys of potential breeding habitat to locate key breeding sites so that these can be afforded appropriate management and additional protection, if required.

- Determine characteristics of wetlands where large flocks occur.

- Encourage (exotic) predator control by Parks Victoria, DELWP and landowners around key breeding wetlands.

- Monitor, on a regular basis, wetlands where flocks of >100 birds have been recorded. This should include ongoing inventory of potential threats to those sites.

- Conduct survey to identify key breeding and flocking sites on PV-managed land and rank according to population size and frequency of use.

- Investigate alternative fishing techniques to prevent by-catch of waterbirds in commercial eel fishing and other activities.

- Determine regularity, seasonality and composition of large flocks and reasons for peaks, including studies of foods.

- Encourage and promote the covenanting of appropriate land through Trust for Nature and promote wetland conservation through the Land for Wildlife scheme.

- Determine the distribution of Blue-billed Ducks in relation to wetlands of varying salinity.

- Continue to conduct annual Summer Waterfowl Counts with assistance from community groups, such as the Field and Game Australia, Birds Australia and local Field Naturalist groups, with a clear objective of locating aggregations of the species.

- Develop a detailed plan involving appropriate community consultation to restore degraded key wetlands for Blue-billed Duck. Mechanisms such as incentive schemes should be considered.

- Involvement of CMA's in the management, restoration and protection of suitable habitats.

Recommendations for creating Blue-billed Duck habitat

Source: (Cull, Newman & Plew 2021)

- A minimum clear, open water distance of at least 140 metres. This cannot be restricted by fringing vegetation such as reeds to tall trees which would then require compensation for the shallow flight ascension or landing angle, significantly increasing the open water distance to allow for this obstacle clearance by the BBD’s. Given the artificial waterbody design requirement for ‘safety’ of a shallow gradient, the potential of this for future overgrowth from reeds and other aquatic vegetation would require that additional calculation to be made in addition to the minimum open water distance, significantly increasing the size of artificial waterbodies for BBD’s.

- Deep water - from a minimum of 1.5 to 2 metres, up to 5 metres for the variety of aquatic plants, insects, invertebrates, etc. that the BBD’s require for feeding - deep and cold water, not shallow and warm, to ensure no future overgrowth by fringing vegetation and less likelihood of drying out during the prolonged drought periods predicted for accelerating climate change.

- A variety of aquatic vegetation such as Ribbon Weed and benthic vegetation such as Eel Grass etc. to encourage and sustain a large variety of seeds and fruits, insects/larvae, invertebrates, etc. for feeding.

- Bull Rush (Cumbungi) for nesting, verging directly onto the deep and open water, for security of the BBD’s in escaping predators in a dive and for close feeding of newly hatched BBD’s. Also for the frequent return to the nest of the young to warm up after diving to feed sessions

- Ideally closed to recreational use, with breeding habitats preferably fenced to keep out predators such as foxes, dogs and cats. Close human contact without fencing disturbs the birds which are seen to retreat 50 to 150 metres away, depending on size of waterbody. Close approach by the birds to people is seen in fenced situations, under the bird’s control. The birds are seen to be aggravated by close human approach without fencing which also discourages nesting and hence disturbed birds leaving the site and no breeding.

References & Links

- AVW (2004) Atlas of Victorian Wildlife, Dept. Sustainability and Environment, Victoria.

- Environment Australia (2000) Action Plan for Australian Birds 2000, Department of Environment, Taxon summary 8211; Blue-billed Duck.

-

Cull, Newman & Plew (2021) Observation Records and Breeding Summary of Blue-billed Ducks Oxyura australis in Victoria from 2015 to mid-2021 Indicating Species Decline. Based on data from VBA – Victorian Biodiversity Atlas, eBird Australia and Birdata (Birdlife Australia) along with Relevant Site Observations, Lake Knox, Victoria. Authors : John Cull, Kevin Newman and Russell Plew, October 2021.

- DELWP (2020) Provisional re-assessments of taxa as part of the Conservation Status Assessment Project – Victoria 2020, Department of Environment Land Water and Planning, Victoria.

- Du Guesclin, P. (2005) personal comment; Department of Sustainability & Environment, Portland.

- Emison W.B., Beardsell C.M., Norman F.I., Loyn R.H. (1987) Atlas of Victorian Birds, Department of Conservation Forests & Lands and Royal Australasian Ornithologists Union, Melbourne.

- FFG Threatened List (2023) Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action (DEECA).

- Flora & Fauna Guarantee, Victoria, Action Statement No.174 Blue-billed Duck

- Hewish M., (1988), Waterfowl count in Victoria February 1988, report prepared for Victorian Dept. Conservation Forests & Lands, Royal Australasian Ornithologists Union, Report No.52,1988.

- IUCN (2022) BirdLife International. 2022. Oxyura australis. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2022: e.T22679827A210733513. h https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/22679827/210733513

- Loyn R.H. (1987) A report on the 1987 duck hunting season in Victoria, National Parks & Wildlife Division, Dept. Conservation Forests & Lands, Victoria.

- Loyn, R. H., Rogers, D. I., Swindley, R. J., Stamation, K., Macak, P. and Menkhorst, P. (2014) Waterbird monitoring at the Western Treatment Plant, 2000–12: The effects of climate and sewage treatment processes on waterbird populations. Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research Technical Report Series No. 256.(pdf) Department of Environment and Primary Industries , Heidelberg, Victoria.

- Marchant S., Higgins P., eds (1990) The Handbook of Australian, New Zealand and Antarctic Birds, Oxford University Press, Melbourne.

- Pain D.J. (1992) Lead Poisoning in Waterfowl: a review. In Lead Poisoning in Waterfowl, proceedings of an IWRB workshop Brussels, Belgium, IWRB special publication No.16, 1992.

- Peter J. (1991) Waterfowl count in Victoria February 1991, report prepared for Victorian Department of Conservation & Environment, Royal Australasian Ornithologists Union, Report No.79,1991

- Purdey, D. and Loyn, R . (2008) Wetland use by Blue-billed Ducks (Oxyura australis) during Summer Waterfowl Counts in North-West Victoria, 1984-2008. Department of Sustainability and Environment: Heidelberg, Victoria.

- Purdey, D. and Loyn, R. (2011) The 2011 Summer Waterbird Count in Victoria. Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research Technical Report Series No. 231, (pdf) Department of Sustainability and Environment, Heidelberg, Victoria.

- Purdey, D. and Loyn, R. (2013) The 2012 Summer Waterbird Count in Victoria. Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research Technical Report Series No. 242, (pdf) Department of Sustainability and Environment, Heidelberg, Victoria.

- Purdey, D. and Menkhorst, P. (2015) Victorian Summer Waterbird Counts: 2014 and 2015. Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research. Unpublished Client Report. Department of Environment, Land, Water & Planning, Heidelberg, Victoria.

- Simpson & Day (1996) Field Guide to the birds of Australia, sixth edition, Penguin Books Australia Ltd.