Black-chinned Honeyeater

Black-chinned HoneyeaterMelithreptus gularis | |

|---|---|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Meliphagidae |

| Status | |

| World: | least concern (IUCN 2024) |

| Australia: | near threatened (Garnett et al. 2010) |

| Victoria: | Not threatened (FFG Threatened List 2025) |

| New South Wales: | vulnerable (Biodiversity and Conservation Act 2016) |

| South Australia: | vulnerable (NPW Act 1972) |

| Queensland | least concern (NCA Act 1992) |

| FFG: | not listed |

The Black-chinned Honeyeater (Melithreptus gularis) is one of three species of white-naped honeyeaters in the genus Melithreptus found in Victoria, others being the Brown-headed Honeyeater Melithreptus brevirostris and the White-napped Honeyeater Melithreptus lunatus. The Black-chined Honeyeater was one of six species of honeyeater listed on the Victorian Threatened Fauna Advisory List (DEPI 2013) but now considered Not threatened (FFG Threatened List 2023).

- Helmeted Honeyeater - Critically endangered

- Regent Honeyeater - Critically endangered

- Grey-fronted Honeyeater - Vulnerable (2013) now Endangered

- Painted Honeyeater - Vulnerable

- Purple Gaped Honeyeater - Vulnerable

- Black-chinned Honeyeater - Near threatened (2013) now Not threatened (2025)

(FFG Threatened List 2025)

Distribution

The Black-chined Honeyeater is a small to medium-sized, olive-backed honeyeater weighing about 20g and around 15.5 cm in length with a stocky build, short tail, and a short, robust and slightly down-curved black bill (Keast 1968; Higgins et al. 2001; Willoughby 2005; Pizzey & Knight 2012). It is distinguished from other Melithreptus honeyeaters by its black cap, black chin, white nape band extending to the eye and blue skin above the eye.

Both sexes are alike; however, juveniles are a duller version of adult birds, with a less conspicuous blue eye apteria, a brown head and an orange bill that darkens to black within their first year (Higgins et al. 2001).

The Black-chinned Honeyeater can be difficult to detect as it is a cryptic honeyeater that moves swiftly through the canopy (Lollback 2007; H.A. Ford, pers. comm. 2014). It's clear, high pitched, gurgling call is heard infrequently (Lollback 2007).

The Black-chinned Honeyeater (south eastern form) Melithreptus gularis gularis range extends from south-eastern South Australia, through Victoria and New South Wales to the Rockhampton area of Queensland where it is replaced by the northern Black-chinned Honeyeater also known as Golden-backed Honeyeater Melithreptus gularis laetior.

BirdLife Australia’s Atlas data suggests that M. g. gularis occupies an area of at least 5,400 km2; however, this estimate is likely to substantially understate the actual extent of occurrence which may be as high as 11,000 km2 (Garnett et al. 2010).

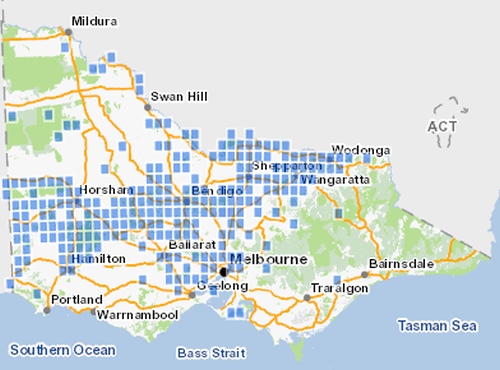

In Victoria, the Black-chinned Honeyeater is mainly found on the northern slopes of the Great Dividing Range.

All known historic records of the Black-chinned Honeyeater in Victoria. Source: VBA 2016

Important Local Government Areas in Victoria for Black-chinned Honeyeater

Note: this is not a full list of LGA's where the Black-chinned Honeyeater has been recorded in Victoria but those with > 50 records.

- Greater Bendigo City - High priority

- Central Goldfields Shire - High priority

- Indigo Shire - High priority

- Northern Grampian Shire - High priority

- Loddon Shire - High priority

- Wangaratta Rural City

- Horsham Rural City

- Strathbogie Shire

- Greater Geelong City

- Moira Shire

- Mount Alexander Shire

- Benalla Rural City

- West Wimmera Shire

- Campaspe Shire

- Southern Grampians Shire

- Greater Shepparton Council

- Hindmarsh Shire

- Ararat Rural City

- Hepburn Shire

- Mitchell Shire

- Pyrenees Shire

- Gannawarra Shire

- Golden Plains

Ecology & Habitat

Habitat requirements

The Black-chinned Honeyeater requires large areas of high quality vegetation (H.A. Ford, pers. comm. 2014; G.W. Lollback, pers. comm. 2014) and is thought to be a habitat specialist (Lollback 2007). It prefers dry, open temperate forests dominated by Box and Ironbark species – which are known to be an abundant source of nectar and invertebrates (Lollback 2007) – as well as River Red Gum Eucalyptus camaldulensis in areas with an annual rainfall of 400-700mm (Garnett et al. 2010; Higgins et al. 2001). Within a fragmented landscape, the species will also utilise paddock trees as a food source (Gibbons & Boak 2002).

Movement

The Black-chinned Honeyeater is regarded as being uncommon (Keast 1968; Ford & Paton 1977; Barrett et al. 2003; Willoughby 2005; Lollback 2007; Lollback et al. 2008; H.A. Ford, pers. comm. 2014) and can be resident or locally nomadic (Higgins et al. 2001). the Black-chinned Honeyeater will traverse open country, over considerable distances, to reach isolated patches of habitat (H.A. Ford, pers. comm. 2014).

Feeding

The Black-chinned Honeyeater forages year round in pairs or tightly-knit social groups (Lollback 2007) of up to 12 birds, seeking out invertebrates and, to a lesser extent, flower nectar (Keast 1968) in the outermost canopy foliage of larger eucalypts (Ford & Paton 1977; Higgins et al. 2001; Willoughby 2005; Lollback 2007; Lollback et al. 2008; Lollback et al. 2010). It will also forage on tree trunks and branches, and occasionally, on the ground and in understorey shrubs (Keast 1968; Ford & Paton 1977; Lollback et al. 2008).

Black-chinned Honeyeaters will occasionally forage with other honeyeater species including, in Victoria, White-plumed Lichenostomus penicillata and Fuscous Honeyeater Lichenostomus fuscus (Higgins et al. 2001, Lollback et al. 2008).

Melithreptus honeyeaters have well-developed ectethmoid-mandibular articulation; a characteristic that enables species in the genus to move both mandibles simultaneously (Lollback 2007; Lollback et al. 2008; Willoughby 2005). This enables the Black-chinned Honeyeater to efficiently prise apart bound leaves in search of its prey, predominantly Lepidoptera larvae, a food source not readily accessible to other honeyeater genera (Lollback 2007). This high degree of specialisation suggests that the foraging niche of the Black-chinned Honeyeater is at a finer scale than that of most other honeyeater species and may explain why this species has a larger home range and travels further to forage (Willoughby 2005; Lollback 2007; H.A. Ford, pers. comm. 2014).

It may also help to explain the Black-chinned Honeyeater’s rarity, in that it feeds on a narrow range of resources that are themselves not abundant (Lollback 2007; Lollback et al. 2008). This may be a disadvantage in fragmented landscapes where resources are sparse or of inferior quality (Willoughby 2005).

Breeding

Breeding is often co-operative and occurs year-round, but most commonly from July to December (Higgins et al. 2001; Willoughby 2005; Garnett et al. 2010; BLA 2014). Pairs build a compact, cup-shaped nest high in the canopy of eucalypts (Higgins et al. 2001).

Threats

The Black-chinned Honeyeater Melithreptus gularis gularis is declining across most of its range, including in Victoria (Garnett et al. 2010).

Major threats include;

Habitat loss & fragmentation of habitat - particularly from the most productive soils in the landscape which are preferred for agriculture (Kyle & Duncan 2012; G.W. Lollback, pers. comm. 2014, (Garnett et al. 2010; Willoughby 2005; Lollback et al. 2010; N. Willoughby, pers. comm. 2014).

Reduced breeding success and low juvenile recruitment (Lollback 2007) due, in part, to the increased predation that occurs along woodland edges (Lollback et al. 2010), as well as stochastic events and interspecific competition from larger or aggressive honeyeater species such as the Noisy Miner (NSWSC 2016; TSSC 2013; Hastings & Beattie 2006; H.A. Ford, pers. comm. 2014).

Anthropogenic climate change - this has the potential to impact on Black-chinned Honeyeater populations whether through variations in the timing and success of breeding, changes to the subspecies’ geographic range, or through a reduction in the availability and nutritional value of food sources (Chambers et al. 2005; Olsen et al. 2007; MacNally et al. 2009; Watson 2011). However, more research is needed to investigate the potential impacts of a changing climate on the Black-chinned Honeyeater, as well as the subspecies’ potential to adapt.

Conservation & Management

The conservation status of Black-chinned Honeyeater was revised from Near Threatened (DEPI 2013) to not threatened (FFG Threatened List June 2021 and (FFG Threatened List June 2025).

Existing conservation measures in Victoria

Reserves

In 2002, Victoria’s National Parks Act (1975) was amended to set aside substantial areas of habitat utilised by the Black-chinned Honeyeater and other woodland species – notably previously under-represented Box-Ironbark and River Red Gum woodlands on the inland slopes of the Great Dividing Range – for conservation and inclusion in Victoria’s Reserve System. These include the St Arnaud Range National Park (now known as the Kara Kara National Park), Greater Bendigo National Park, Chiltern-Mt Pilot National Park, and Heathcote Graytown National Park, among others (GV 2014). For the most part, however, these Reserves are on poorer soils and less than optimal habitat for the Black-chinned Honeyeater.

Native vegetation protection

In Victoria, the removal of native vegetation is regulated under the State’s Planning Scheme, and more specifically, by the Native Vegetation Permitted Clearing Regulations. These regulations require that a permit be obtained to remove, destroy or lop native vegetation and that, where a permit is granted, an offset of equivalent vegetation type, amount and attributes is required (DELWP 2016).

Habitat management projects

A range of projects and programs are undertaken on an ongoing basis throughout Victoria by conservation groups and natural resource managers including Landcare, Conservation Management Networks, NGOs e.g. Birdlife Australia and similar organisations and volunteer bodies. While not specifically targeting Black-chinned Honeyeaters, these projects and programs benefit a range of species in Victoria’s temperate eucalypt woodlands by expanding and rehabilitating habitat and restoring landscape connectivity.

Suggested conservation objectives

Long-term objective (> 10 years)

Through habitat protection, restoration and expansion, stabilise populations of the Black-chinned Honeyeater in Victoria to ensure survival of the subspecies over the long term.

Management actions

1) Habitat expansion and enhancement

- Identify and protect areas of high-quality Black-chinned Honeyeater habitat, particularly patches containing mature eucalypts;

- Initiate, promote and support large-scale revegetation and rehabilitation programs aimed at enhancing and expanding key Black-chinned Honeyeater habitat and increasing connectivity in the landscape, with a particular focus on private land where soils are generally fertile and more productive; and

- For revegetation projects within the Black-chinned Honeyeater’s range, encourage plantings of eucalypt species utilised and preferred by the Black-chinned Honeyeater such as River Red Gum Eucalyptus camaldulensis, Box (e.g. Eucalyptus albens, Eucalyptus melliodora and Ironbark e.g. Eucalyptus sideroxylon along with shrubby understorey species, including bipinnate acacias, to minimise aggression and resource domination by Noisy Miners (Hastings & Beattie 2006).

2) Research and monitoring

- As a priority, initiate research and monitoring programs of Black-chinned Honeyeater populations in Victoria to gain a better understanding of the subspecies’ ecology as relevant to potential cause(s) of its decline. To date, most research has been undertaken in New South Wales and South Australia. Such research would investigate population size, breeding success, differences in habitat and resource utilisation from elsewhere in the Black-chinned Honeyeater’s range, as well as seasonal movements, and the impact of interspecific competition and other threatening processes.

- Using the latest climate trend data, model the potential impact of global warming on the food resources of Melithreptus honeyeaters, including the Black-chinned (N. Willoughby, pers. comm. 2014).

3) Public education

Through community education:

- Raise public awareness of the Black-chinned Honeyeater, including species ecology, current conservation status and habitat requirements to empower conservation at a local level.

- Encourage the retention and protection of remnant native woodland and mature eucalypts on private land within the Black-chinned Honeyeater’s existing range.

4) Public policy and regulation

- Strictly control and regulate the collection and removal of firewood from native forests within the Black-chinned Honeyeater’s range.

- Tighten the Native Vegetation Permitted Clearing Regulations to strictly limit the removal of mature eucalypts, including trees in remnant woodland and scattered paddock trees.

- Introduce incentive programs and other mechanisms to promote the protection and expansion of native habitat on private land (Kyle & Duncan 2012).

References & Links

- Barrett G.W., Silcocks A.F., Barry S., Poulter R. & Cunningham R.B. (2003) The New Atlas of Australian Birds. Birds Australia, Melbourne.

- BirdLife Australia (2016) Black-chinned Honeyeater. [Cited 11 January 2016.]

- BirdLife Australia (BLA) (2005-2007) Birdata Database. The Atlas of Australian Birds. BirdLife Australia, Melbourne. [Cited 8 March 2017.]

- Chambers L.E., Hughes L. & Weston M.A. (2005) Climate change and its impact on Australia’s avifauna. Emu. 105, 1-20.

- Department of Environment, Land, Water & planning (DELWP 2016) Native vegetation permitted clearing regulations. [Cited 11 January 2016.]

- Department of Environment & Primary Industries (DEPI 2013) Advisory List of Threatened Vertebrate Fauna 2013. [Cited 11 January 2016] Advisory-List-of-Threatened-Vertebrate-Fauna_2013.

- FFG Threatened List (2025) Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action (DEECA).

- Ford H.A. & Paton D.C. (1977) The comparative ecology of ten species of honeyeaters in South Australia. Australian Journal of Ecology. 2, 399-407.

- Garnett S.T., Szabo J.K. & Dutson G. (2011) The Action Plan for Australian Birds 2010. CSIRO Publishing, Melbourne. Species profile- Black-chinned Honeyeater. Page 503.

- Gibbons P. & Boak M. (2002) The value of paddock trees for regional conservation in an agricultural landscape. Ecological Management and Restoration. 3, 205-210.

- Government of Victoria (GV) (2014) National Parks (Box-Ironbark and Other Parks) Act 2002. [Cited 17 September 2014.] http://www.legislation.vic.gov.au/

- Hastings R.A. & Beattie A.J. (2006) Stop the bullying in the corridors: Can including shrubs make your revegetation more Noisy Miner free? Ecological Management & Restoration. 7, 106-112.

- IUCN (2024) BirdLife International. 2024. Melithreptus gularis. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2024: e.T22704143A253982570. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2024-2.RLTS.T22704143A253982570.en. Accessed on 03 April 2025.

- NCA Act (1992) Nature Conservation Act 1992, Nature Conservation (Wildlife) Regulation 2006, Current as at 28 August 2015. Department of Environment & Heritage Protection, Queensland. [Cited: 11 January 2016]

- Higgins P.J., Peter J.M. & Steele W.K. eds (2001) Handbook of Australian, New Zealand and Antarctic Birds. Volume 5: Tyrant-Flycatchers to Chats. Oxford University Press, Melbourne.

- Keast A. (1968) Competitive interactions and the evolution of ecological niches as illustrated by the Australian honeyeater genus Melithreptus (Meliphagidae). Evolution. 22, 762-784.

- Kyle G. & Duncan D.H. (2012) Arresting the rate of land clearing: Change in woody native vegetation cover in a changing agricultural landscape. Landscape and Urban Planning. 106, 165-173.

- Lollback G.W. (2007) Ecology of an uncommon species, the black-chinned honeyeater (Melithreptus gularis gularis), in north-eastern New South Wales (PhD Thesis). University of New England, NSW.

- Lollback G.W., Ford H.A. & Cairns S.C. (2008) Is the uncommon Black-chinned Honeyeater a more specialised forager than the co-occurring and common Fuscous Honeyeater? Emu. 108, 125-132.

- Lollback G.W., Ford H.A. & Cairns S.C. (2010) Recruitment of the Black-chinned Honeyeater Melithreptus gularis gularis in a fragmented landscape in northern New South Wales, Australia. Corella. 34, 69-73.

- MacNally R., Bennett A.F., Thomson J.R., Radford J.Q., Unmack G., Horrocks G. and Vesk P.A. (2009) Collapse of an avifauna: climate changes appears to exacerbate habitat loss and degradation. Diversity and Distributions. 15, 720-730.

- NSW Scientific Committee (NSWSC 2016). Black-chinned honeyeater (eastern subspecies) – vulnerable species listing. Final determination. (Office of Envionment & Heritage) [Cited 11 January 2016].

- (NPW Act 1072) National Parks and Wildlife Act 1972, South Australia. Vulnerable species—Schedule 8, 1.7.2015.

- Olsen P. (2007) The State of Australia’s Birds 2007: Birds in a Changing Climate. Supplement to Wingspan. 14, no. 4.

- Olsen P., Weston M., Tzaros C. & Silcocks A. (2005) The State of Australia’s Birds 2005: Woodlands and birds. Supplement to Wingspan. 15, no. 4.

- Pizzey G. & Knight F. (2012) The Field Guide to the Birds of Australia, 9th edn. HarperCollinsPublishers, Sydney.

- (VBA 2016) Victorian Biodiversity Atlas, Department of Environment, Land, Water & Planning (DELWP), Victoria. [Accessed 11 January 2016].

- TSSC (2013) Threatened Species Scientific Committee, Advice to the Minister for Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population & Communities from the Threatened Species Scientific Committee (the Committee) on Amendments to the List of Key Threatening Processes under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act), 6 March, 2013.

- Watson D.M. (2011) A productivity-based explanation for woodland bird declines: poorer soils yield less food. Emu. 111, 10-18.

- Willoughby N. (2005) Comparative ecology, and conservation, of the Melithreptus genus in the Southern Mount Lofty Ranges, South Australia (PhD Thesis). University of Adelaide, South Australia.

Contributors

This page has been adapted from material provided by D. Saxon-Campbell, Federation University - Australia, who received contributions from

- Emeritus Prof. Hugh Ford, School of Environmental and Rural Science, University of New England, Armidale NSW.

- Dr Greg Lollback, Research Fellow, School of Environment, Griffith University (Gold Coast campus), Queensland.

- Dr Nigel Willoughby, Ecologist, South Australian Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources.

More Information

- BirdLife Australia - Black-chinned Honeyeater

- Adelaide and Mt lofty Ranges Threatened species profile - Black-chinned Honeyeater pdf

Please contribute information regarding the Black-chinned Honeyeater in Victoria - observations, images or projects. Contact SWIFFT