Brown Toadlet

Brown Toadlet (Bribron's Toadlet)Pseudophryne bibronii | |

|---|---|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Amphibia |

| Order: | Anura |

| Family: | Myobatrachidae |

| Status | |

| World: | Near threatened (IUCN 2004) |

| Australia: | Not listed (EPBC Act) |

| Victoria: | Endangered (FFG Threatened List 2025) |

| Victorian FFG: | Not listed |

Image: Peter Robertson.

The Brown Toadlet Pseudophryne bibronii, also known as Bibron’s toadlet, is a small brownish coloured toadlet only 2 - 3 cm long. It is endemic to south-eastern Australia including Tasmania and is found in a variety of habitats not necessarily associated with permanent water.

The Brown Toadlet is found from south-eastern Queensland, through eastern NSW, central Victoria, eastern South Australia to Kangaroo Island and eastern Tasmania ( Hoser 1989, Hero et al.1991). it is considered to be the most widespread of its genus (Hero 1991) and covers an estimated area of 721,300 km2 and occurs at elevations from between 20-1000 metres above sea level (Anon 2006).

The Brown Toadlet is brown to black on its back, with a scattering of darker flecks and red spots. Its underbelly is marbled black and white and there is a bright yellow patch around its cloaca. A faded yellowish stripe usually occurs down the middle of its lower back. On the base of each arm there is always an orange or yellow patch. The skin on the back is smooth and usually scattered with a few tubercles (warts), while the belly is either smooth or slightly granular. Its toes are not webbed and it tends to moves by walking. Adult female toadlets are slightly larger than males, measuring between 25-32mm, compared to the male toadlets 22-30mm length (Walker et al. 1999, Gillespie et al 2004, Anon 2005).

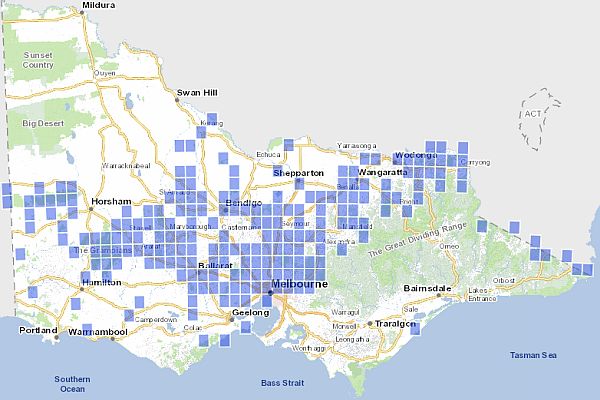

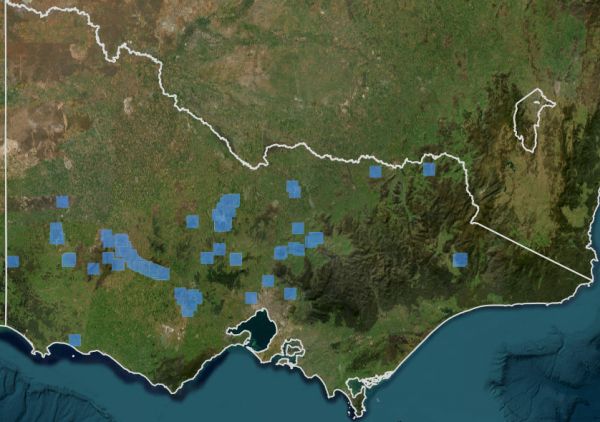

Distribution

In Victoria, the Brown Toadlet is distributed from the north-east through to central and western Victoria with scattered records in Gippsland. To the north of Melbourne there are many historic records from Diggers Rest across to Craigieburn and Warrandyte, however there has been a marked decline in these populations in recent years.

In Victoria's south-west most records are grouped on the Volcanic Plains bioregion north of Werribee, the Greater Grampians bioregion and the Lowan Mallee bioregion in the Little Desert.

Ecology & Habitat

The Brown Toadlet utilises a wide variety of habitats, including dry forests, woodland, shrubland, grassland, coastal swamps, heathland, and sub-alpine areas (Anon 2006). They live in areas that are likely to be inundated after rain (Robinson 2002). They shelter in damp areas under leaf litter, logs, or other forms of cover.

Hydrology is critical for Bibron's Toadlet persistence within an area, because the species requires the presence of ephemeral water bodies that hold water for at least 5 months of the year (Anstis 2002, Howard et al. 2010, Terry 2017, De Angelis 2021).

The Brown Toadlet is likely long-lived, up to 9 years (Hunter 2000) and capable of aestivating in surface soil to endure particularly dry conditions (Thompson et al. 2003; Frogwatch SA 2024).

It is thought that within its broad geographical distribution, the local distribution of the Brown Toadlet may be influenced by soil pH, with a preference for low soil pH. A study by Chambers et al. (2006) found that soil pH at sites where P. bibronii were recorded as present was significantly lower than pH at sites where P. bibronii were recorded as absent. They conclude soil pH and/or fungi associated with high-pH soils (>5) may play a major role in influencing the local distribution of this species.

Breeding

The breeding season is autumn (March to May) when males initiate breeding by calling from nest sites. Calling activity by Brown toadlet males may begin in February and continue through until August (Natureserve 2006). Males call in response to seasonal and environmental triggers, with the most intense calling on still evenings, after rain in April to early May (Howard et al 2010).

The males call from within a burrow or nest (a concealed area under a rock or log, or within damp leaf-litter) near water (Robinson 2002). The structure of the call by the male is variable, and can be described as a grating “ark” sound, or a short, grating “cre-ek” noise and the call is repeated every few seconds. (Gillespie et al. 2004; Anon 2006). Distinguishing the call from the Southern Toadlet is virtually impossible.

Females are believed to have a minimum reproductive age of less than 2 years, and lay only one batch of eggs each breeding season (Anon 2005).

Eggs are deposited in the nest at the calling site, either under moist leaf litter, in sphagnum moss, or under stones or logs, near water, or nearby in a concealed place near water. Eggs are large and pigmented, and are spawned in loose clumps of between 70-200 eggs. When rain floods the nest site, these eggs hatch and the tadpoles develop in the water. Tadpoles vary in colour from dark brown to grey, and the clear tail fin is mottled with black or brown flecks. However, if rain does not occur soon after laying, the eggs can survive unhatched for many weeks, and the tadpoles begin to develop inside these unhatched eggs. Metamorphosis takes between 3-7 months (Pengilley 1973, Anon 2005, (Gillespie et al. 2004).

Decline

Declines in Victoria are occurring co-currently with declines in other states. (Hazel 2001). Currently, the specific reasons for many of the reported declines are not known.

A survey of the Greater Melbourne district for the Melbourne Water frog census failed to find the species at any of the 40 sites where it had previously been found. A decline in records inVictoria's Biodiversity Atlas also suggests that the species has reduced in numbers and their range has contracted. It has been predicted that the Brown Toadlet is in significant decline, at a rate of less than or equal to 30% over ten years (IUCN 2006).

In March to May 2010, surveys of 106 sites were sampled in for Bibron’s Toadlets (Brown Toadlets) in response to 2009 Black Saturday Bushfires. The surveys were conducted the vicinity of Darraweit Guim in the west, to Yea in the north, Buxton in the east and Wonga Park in the south. Only two Bibron’s Toadlets (Brown Toadlets) were detected, both in unburnt area. However, researchers noted that it was likely Bibron’s Toadlets had already undergone severe declines in at least some parts of the study area well before the fires, possibly due to many years of below average rainfall (Howard et al 2010).

Targetted surveys for Bibron's Toadlet were carried out in 2024 at five priority sites containing historic records within the Melbourne Water region but no detections were found. There is a possibility that Bibron's Toadlet may now be locally extinct in the greater Melbourne area. (Jury et al. 2025).

Threats

Major threats can be categorised as; changed hydrology, climate change, chytrid fungus and urban/agricultural sprawl (Cleeland 2023).

Habitat alteration and degradation - possible causes:

- Livestock and high grazing intensities.

- Cropping.

- Infrastructure development.

- Previous and current mining activities.

Waterway degredation, possible causes:

- Increasing salinity

- High nutrients and sediments in waterways

- Waterway weeds such as willows

- Changes to hydrology (groundwater pumping, altered flow patterns, drainage).

Other potential threats possible causes:

- Global and regional climate change, including the current drought.

- Chytrid fungus.

- Land and atmospheric pollution.

- Pest animal species such as cats, foxes, dogs etc.

- Predation of tadpoles by fish

- Small population sizes, which makes populations more susceptible to localised extinctions

Note: Eastern Gambusia presents a higher threat to Bibron's Toadlet at sites where tadpole maturation is reliant on a central pond or catchment.

Suggested conservation maeasures in Victoria

The overall and long term objective should be to guarantee that the Brown Toadlet survives and prospers in the wild, and maintains it’s potential to evolve.

1. Accurately measure Brown Toadlet numbers, locations and habitats of existing populations.

- Develop a statistically sound method for assessing and comparing population sizes and habitat.

- Undertake population and habitat monitoring.

- A statistically accurate long-term study is required to distinguish between natural fluctuations in populations and serious declines. Currently, there is not a very accurate idea of the total number of individuals of the species, and this is needed to measure future declines from. Also, as individual toadlets occur over a large range of habitats, a habitat survey along with the population study will show which type of habitat supports the largest populations of Bibron’s toadlets, as well as which habitats they are failing to thrive in as well. This will give a better indication as to which habitat communities to protect, as well as which populations are likely to be at the biggest risk.

- Provide this information to Catchment Management Authorities, local government authorities, land managers and landholders as required.

Responsibility for population monitoring: DEECA, Parks Victoria, VicForests, Melbourne Water.

2. Determine the exact cause/s responsible for the current decline of the Brown Toadlet.

- Develop a method for studying populations to determine the impacts of believed threats, and carry this out.

- Provide this information to Catchment Management Authorities, local government authorities, land managers and landholders as required.

Responsibility: DEECA, Parks Victoria.

3. Reduce the impact of known threatening processes to Brown Toadlet habitat.

- Integrate habitat improvement with existing programs such as pest plant and animal control and salinity reduction projects.

- Continue to work on improving water quality (This can involve working with landholders to fence off their stock from rivers and creeks, creek bank revegetation, implementing sediment traps in waterways, willow removal etc.).

- Evaluate proposed infrastructure developments for possible effects on the Brown Toadlet before they are carried out (This will prevent accidental harm to the species, and will allow compensatory measures to be put into place where required).

Responsibility: DEECA, Parks Victoria, Local Government, relevant Catchment Management Authorities & Water Authorities.

4. Planning to protect known Brown Toadlet habitats.

- Incorporate actions to protect Brown Toadlet habitat into relevant Regional Catchment Strategies, through Biodiversity Action Plans, Local Landscape Plans, Biodiversity Maps and Municipal Planning Scheme environmental overlays.

Responsibility: DEECA, Parks Victoria, Local Government, relevant Catchment Management Authorities & Water Authorities.

Recent surveys

Macedon Ranges Shire has undertaken surveys in many of its reserves. Detection of the Brown Toadlet at Bald Hill Reserve, near Kyneton in 2016 was significant as it had not been recorded in the area for over 20 years. Using the Amphibian Calling Index technique, the species was detected at five sites in the Reserve. Peak activity occurred during April and May, while no P. bibronii were recorded calling in June. This survey suggests the Bald Hills Reserve is a significant site for this species (Terry 2017).

In 2021, surveys for Bribon’s Toadlet were carried out at Seymour Bushland Park, (Approx. 35 km north of Melbourne in Mitchell Shire which found a viable population (De Angelis, D. 2021).

In 2024, surveys for Bibron's Toadlet were carried out at five priority sites containing historic records within the Melbourne Water region but no detections were found indicating the possibility that Bibron's Toadlet could now be locally extinct in the greater Melbourne area. (Jury et al. 2025). More details

Habitat enhancements

Summary adapted from: Jury, G., Young, D., & Allan, L. (2025) Targeted Survey Report Potential Bibron’s Toadlet Sites in the Melbourne Water Catchment. Prepared for Melbourne Water Version 1.1. March 2025 by TREC Land Services

Management actions should be immediately triggered within suitable habitat by a confirmed current Bibron's Toadlet observation within 5 km.

Hygiene

Hygiene protocols should include: sterilisation of footwear, tools and vehicles entering breeding habitat, and attention to hygiene during activities that risk introducing foreign soil; e.g., planting. Limit public access (and stock, if within agricultural land) to potential breeding habitat through signage, track design and fence installation.

Hydrology

Allow surface water to pool over late autumn and winter, with standing water gradually subsiding over late spring to mid-summer (De Angelis 2021). During the dry season, surface soil moisture may vary in response to weather conditions but should not produce persistent standing water until at least May.

Stream beds can form Bibron's Toadlet breeding habitat as well as still water areas. To improve the potential for toadlets to reoccupy available habitat, consider the restoration and protection of still-water wetlands and flood runners, as well as encouraging creeks to meander, through selective planting and addition of coarse woody debris.

Bibron's Toadlet breeding habitat can be enhanced/extended if necessary, by creating shallow, clay lined pits (approximately 80 cm deep and 150–300 cm wide). These pits should hold water for ~5–7 months of the year, with the water level artificially manipulated if necessary.

Trees and woody vegetation within 100 m of designated breeding habitat should be thinned to increase surface soil moisture, encouraging the formation of ephemeral standing water with a hydro period of 5–7 months.

Vegetation

Breeding habitat

An open and low biomass sward forms a core part of the breeding habitat. Vegetation within 100 m of potential breeding habitat should be maintained at a low height (≤ 15 cm)

Rock piles and logs contribute to this habitat function.

Non-breeding refugia

Denser patches of higher biomass vegetation (e.g., tussock grasses Poa spp., Kangaroo Grass, maidenhairs spp.) within 100–250 m of breeding habitat to provide critical non-breeding refugia for toadlets. Rock piles and logs contribute to this habitat function.

Recommendations for future surveys in Melbourne Water catchment

Jury, G., Louise Allan, L., & Hall, C. (2025) Habitat Assessment Report Potential Bibron’s Toadlet Sites in the Melbourne Water Catchment. Prepared for Melbourne Water Version 1.0. May 2025 Summary of priority sites

References & Links

Anon (2005) Pseudophryne bibronii . Australian Frog Database. Frogs Australia Network. Victoria.

Anon (2006) Pseudophryne bibroni: Bibron's Toadlet. Frogs of Australia.

Chambers, J., Wilson J.C., Williamson I. (2006) Soil pH influences embryonic survival in Pseudophryne bibronii (Anura: Myobatrachidae) Austral Ecology, Volume 31, Issue 1: 68-75. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9993.2006.01544.x

De Angelis, D. (2021). Surveys and management considerations for the Brown Toadlet Pseudophryne bibronii at Seymour Bushland Park and the former Seymour Motocross Track. ABZECO report 21024.1, Version 1.0.

DeAngelis, D. & Cleeland, C. (2023). Interim survey guidelines for toadlet Pseudophryne species in Victoria. Version 1.0. Ecological Consultants Association Victoria.

FFG Threatened List (2025) Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988 - Threatened List - September 2025, Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action (DEECA) , Victoria.

Hero, J-M., Gillespie, G., Lemckert, F., Littlejohn, M. & Robertson, P. (2004) Pseudophryne bibronii IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Accessed 17 May 2016.

Hazel, D., Osborne, W. & Lindenmayer, D (2003) Impact of post-European stream change on frog habitat: south-eastern Australia. Biodiversity and Conservation 12: 301-320

Hero, J-M., M. Littlejohn and G Marantelli (1991) Frogwatch Field Guide to Victorian Frogs. Department of Conservation & Environment, Victoria.

Hoser, R.T. (1989) Australian Reptiles & Frogs, Pierson & Co, Sydney, Australia.

Jury, G., Young, D., & Allan, L. (2025) Targeted Survey Report Potential Bibron’s Toadlet Sites in the Melbourne Water Catchment. Prepared for Melbourne Water Version 1.1. March 2025 by TREC Land Services

NatureServe (2006) Pseudophryne bibronii - Bibron's Toadlet, Brown Toadlet. Amphibian Survival Alliance.

Pengilley, R. (1973) Breeding Biology of some Species of Pseudophryne (Anura: Leptodactylidae) of the Southern Highlands New South Wales. Australian Journal of Zoology 18(1): 15-30.

Robinson, M. (2002). A Field Guide to Frogs of Australia. Australian Museum/Reed New Holland: Sydney

Terry, W. (2017) The Brown Toadlet 'Pseudophryne bibronii' (Anura: Myobatrachidae), at Bald Hill Reserve, Kyneton, Victoria [online]. Victorian Naturalist, The, Vol. 134, No. 4, Aug 2017: 96-100. Abstract Informit.

Tyler, M.J. (1997) The Action Plan for Australian Frogs. Environment Australia, Canberra.

VBA (2025) Victorian Biodiversity Atlas, Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action (DEECA), Victoria.

VVB (2025) Visualising Victoria's Biodiversity map portal

Walker, S.J., Hill, B.M., & Goonan, P.M (1999) Frog Census-a Report on Community Monitoring of Water Quality and Habitat Conditions in South Australia using Frogs as Indicators. Environment Protection Agency. Department for Environment and Heritage