Masked Owl

Masked OwlTyto novaehollandiae novaehollandiae | |

|---|---|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Strigiformes |

| Family: | Tytonidae |

| Status | |

| World: | Least concern (IUCN Red List 2023) |

| Australia: | Not listed |

| Victoria: | Critically endangered (FFG Threatened list 2024) |

| Profiles | |

| Victoria: | FFG Action Statement No. 124 |

The Masked Owl is regarded as possibly being one of the least known owl species in Australia. Its nocturnal and secretive behaviour includes long periods at night without calling during the non breeding season and aversion to light, which make this species difficult to detect and study.

The Masked Owl Tyto novaehollandiae occurs in both Australia and New Guinea, possibly six subspecies are thought to exist, although some may warrant species status:

- Tyto novaehollandiae castanops (Tasmania) - Vulnerable EPBC Act

- Tyto novaehollandiae galei (far north Queensland)

- Tyto novaehollandiae kimberli (northern Australia) - Vulnerable EPBC Act

- Tyto novaehollandiae melvillensis (Melville Island, Northern Territory) - Endangered EPBC Act

- Tyto novaehollandiae novaehollandiae (southern Australia from Western Australia to Queensland) although there is a possibility the Western Australia population may be sub-specifically distinct).

(Higgins 1999, Debus 2002, AFD 2023)

The Masked Owl has a facial mask which is similar to the more commonly recognised Barn Owl, this being a feature of the genera Tyto. The Masked Owl has a stocky, often crouched posture, strong heavy feet and feathered legs. Its facial disk has a blackish-brown edge, with rufous or brown colouring around the eyes. Three colour morphs are recognised which may occur within each sub-species. Dark, Intermediate and Light morphs are determined by the colour of the facial disk and toning of the plumage. Victorian records have included all three colour morphs (Peake et al. 1993).

Females are generally darker in colour and larger than males (females (47 cm ), (males 37cm). Care needs to be taken to avoid miss-identification of Intermediate or Light morph colour males which are similar in colour and size to the Barn Owl. The Masked Owl’s call is described as a long rasping screech and also a strong harsh hissing – ‘kwooosh’ (Simpson & Day 1999, Viridans 2005).

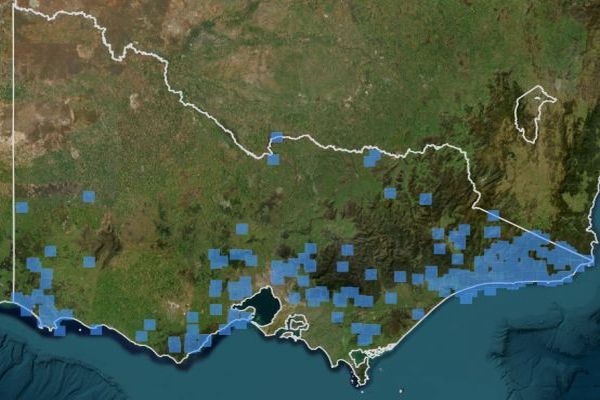

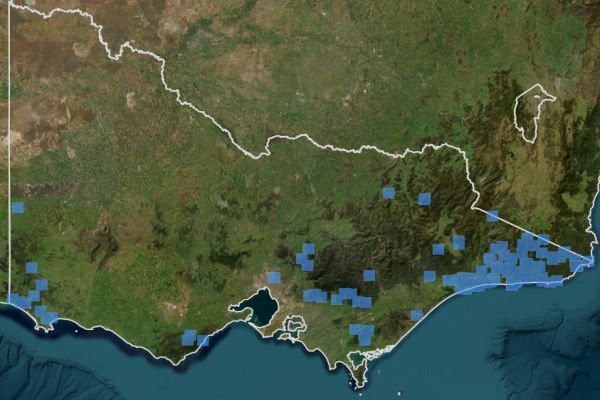

Distribution

In Victoria, most records of Masked Owl Tyto novaehollandiae novaehollandiae are from East Gippsland, there are however three significant concentrations of records within the South West region; the Otway Ranges (Otway Ranges Bioregion) and to a lesser extent in the Midlands (Central Victorian Uplands Bioregion) and Portland area (Glenelg Plain Bioregion) (VBA 2023). A significant record of successful breeding in the South West region was recorded near Corndale in 1999 (McNabb et al. 2003).

Ecology & Habitat

Habitat

Masked Owl habitat varies to some extent across its geographic range and in response to vegetation communities, vegetation structure and landscape. They are found across a range of habitats from wet sclerophyll forest, dry sclerophyll forest, non eucalypt dominated forest, scrub and cleared land with remnant old growth trees.

There are several aspects of habitat preference which appear to be common:

- large hollows in old growth eucalypts for nesting

- dense understorey or ecotones comprising dense and sparse ground cover, they are often recorded foraging within 100-300m of the boundary of two vegetation types.

- areas near gullies and along watercourses are frequently used, possibly because these habitats provide a greater diversity of prey species. (Peake et al. 1993, Kavanagh 1996, Kavanagh & Murray 1996, Bell & Mooney 2002)

The predicted occupancy of Masked Owls in an area of suitable habitat may have more to do with the availability of prey species than the quality of the habitat. (Cisterne et al. 2020)

Habitats in the Otway Ranges and Midlands incorporate floodplains, creek-flats and to a lesser extent gullies. These include riparian forests – Manna Gum or to much lesser extend Swamp Gum , damp sclerophyll forest Mountain Grey Gum, wet sclerophyll forest Mountain Ash with Messmate.

At other locations records comprise Manna Gum woodland on the Dundas Tablelands near Nareen, Manna Gum woodland–farmland at Stoney Rises, Red Gum in open farmland near Corndale and Casterton, Sheoak and eucalypts near Portland. Farmland sites appear to be grazing rather than cropping land (Peake et al. 1993, McNabb et al. 2003). Surveys carried out in Tasmania indicate that rainforest or pine plantations may not be utilised (Bell & Mooney 2002)

Breeding

The breeding season extends from about April through to November and owls are most vocal for short periods early in the breeding season. One sometimes 2 fledging owlets are raised with fledglings leaving the nest in December.

There are only 5 nesting records in Victoria including one in the south west of Victoria near Corndale, recorded in 1999. Nests are dependent upon suitable large hollows or vertical holes (ie 1-3m deep and .5m wide) within the trunk of mature or dead eucalypts. Nest hollows may also be used for roosting during non-breeding season, at other times roosting can be in live or dead trees which provided suitable hollows, also they have been known to sometimes roost in caves (Peak et al. 993, Kavanagh 1996). Observations in Western Victoria indicate they tend to remain inside roost hollow until well after sunset, particularly on bright evenings (McNabb et al. 2003).

Home range

The Masked Owl has a home range in excess of 1000 hectares, up to 1310 hectares has been calculated from studies in the in the South West region (McNabb et al. 2003).

Feeding

Diet is influenced by habitat, for example within forests it mainly consists of small native mammals, Bush Rat and Antechinus comprising the highest proportion of prey, to a lesser extent small gliders & Ring Tailed Possums, birds & beetles. Areas around the forest edge and in more human modified landscapes such as semi urban or rural areas diet may comprise or be predominantly introduced species eg. Rabbit, Black Rat, House Mouse (Peak et al 1993, Kavanagh & Murray 1996).

Detection of prey is enhanced by the concave shape of the face which collects sound over the entire face and guides sound to each ear. The ears are located above the eyes and covered by a skin flap with densely packed feathers. The ears are positioned at slightly different vertical heights (asymmetrical) which enables improved hearing with less reliance on sight for accurate detection of prey (Norberg 2002).

Population Status

The overall status of Masked Owl Tyto novaehollandiae is considered stable (IUCN 2023) and its conservation status being Least concern. However, the population of the sub-species Tyto novaehollandiae novaehollandiae which occurs in Victoria is considered Critically endangered, being not as stable, reducing in distribution and possibly suffering a major decline in East Gippsland following the 2019/2020 bushfires. The full extent of population change in East Gippsland is still being determined by undertaking landscape scale surveys of fauna.

Threats

A major threat to the Masked Owl and other hollow dependent fauna including the owl’s prey species is the loss of both mature and dead trees which contain hollows.

Fire protection

Trees at high risk are often near forest margins and on privately owned forested or farmland areas that may be subject to loss through fire or wind damage. Fire prevention activities which may include accidental burning or ‘tidying up’ operations involving pushing over dead trees severely degrades habitat. In parts of western Victoria, old growth Red Gums play a particularly important role in cleared or semi cleared landscapes by providing nesting/roosting hollows.

Poisoning

In areas where habitat for native species has been removed through clearing the owl’s diet may have become dependent upon introduced prey species such as rabbits, mice or rats. Eradication programs conducted on a large scale eg. rabbits’ eradication programs may have unintended consequence for Masked Owls through loss of food source, particularly during the owl’s breeding season. Eradication of rodents at a local level, particularly where owls are known to exist may increase chances of secondary poisoning depending on the type of rodenticide and methods used.

Road kill

Habitat fragmentation and loss of feeding areas may place more reliance on foraging in areas such as road reserves where there is a greater probability of being hit by vehicles.

Firewood collection

Habitat loss in forested areas through loss of hollow bearing trees and loss of habitat for prey species. The removal of dead trees and logs on the ground by firewood collection removes habitat for prey species and in turn deprives the owl from its natural food source.

Conservation & Management

A full list of proposed actions is contained in the Flora & Fauna Guarantee Action Statement No. 124 pdf

The impact of plantations surrounding known roost/nest trees and need for further studies regarding feeding along edges of plantations has been raised as an issue requiring further investigation (Mc Nabb et el 2003).

Logging

The Victorian Regional Forest Agreements incorporated protection measures for the Masked Owl which include; within a 3km radius of a confirmed record, approx. 500 Ha of suitable habitat will be reserved from timber harvesting in the form of special protection zones (SPZ) or Masked Owl management areas (MOMA’s). (RFA 2000). In several areas of Victoria, the SPZ’s and MOMA’s have been superseded to some extent due to the cessation of logging and creation of new parks now under Parks Victoria management. However, recognition of special management areas is still be important within the parks to ensure requirements of the Masked Owl are taken into account

Specific Actions for conservation of the Masked Owl

- These are the responsibility of land managers such as Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action (DEECA), Parks Victoria, Local Government and private landholders.

- Encourage and assist Municipal Councils to develop conservation mapping and Geographic Information Systems overlays within planning schemes to improve information on owl habitat and breeding sites across private land.

- Monitor all known Masked Owl habitat sites within the parks and reserves system as a contribution to target numbers of regional Masked Owl Management Areas (MOMAs).

- Record habitat attributes of known Masked Owl sites in order to contribute to the development of a habitat model for the species, similar to those which have been developed for Powerful and Sooty Owls. (Loyn et al. 2002).

- Conduct targeted surveys across all land tenures to locate as many resident pairs of Masked Owls as possible across land tenures throughout the main range of the species.

- In smaller conservation reserves, protect as much suitable habitat as possible and endeavour to obtain co-operative management from adjoining landowners.

- Protect all known Masked Owl habitat sites within the parks and reserves system as a contribution to target numbers of regional MOMAs. In larger parks and reserves delineate MOMAs of at least 500 ha of continuous suitable habitat which can be managed so as to be free of significant disturbance factors. In smaller conservation reserves, protect as much suitable habitat as possible.

- Protect Masked Owl habitat in State forest according to protocols and prescriptions in Action Statement.

- Assess habitat characteristics and/or condition and habitat elements used by Masked Owls to determine their importance and assess the need to focus conservation efforts on those elements.

- Monitor selected MOMAs, and all known breeding sites, at suitable intervals, to determine persistence of owls and breeding success.

Projects & Partnerships

Landscape Scale Survey Program

In response to the 2020 bushfires, ARI’s researchers are undertaking extensive surveys of 53 priority forest-dependent species across eastern Victoria – ARI 2019. Bushfire response 2020 - impacts on gliders and owls

References & Links

Bell, P.J. & Mooney, N. (2002) Distribution, Habitat and Abundance of Masked Owls (Tyto novaehollandiae) in Tasmania, In; Ecology and Conservation of Owls, Eds. Newton I., Kavanagh R., Olsen J., & Taylor I., CSIRO Publishing, Australia.

Cisterne, A., Crates, R., Bell, P., Heinsohn, R. and Stojanovic, D. (2020) Occupancy patterns of an apex avian predator across a forest landscape, Austral Ecology (2020) 45, 825–833

Debus, S. (2002) Distribution, Taxonomy, Status and major threatening processes of owls of the Australasian Region, In; Ecology and Conservation of Owls, Eds. Newton I., Kavanagh R., Olsen J., & Taylor, I., CSIRO Publishing, Australia.

FFG Threatened list (2024) Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988 - Threatened List - June 2024 Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action (DEECA), Victoria.

Higgins, P.J. (ed.) (1999) Handbook of Australian, New Zealand and Antarctic Birds, Vol. 4. Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

IUCN (2023) BirdLife International. 2018. Tyto novaehollandiae. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2018: e.T62172196A132190

Kavanagh, R. P. (2002) Conservation and management of large forest owls in southeastern Australia. In; Ecology and Conservation of Owls, Eds. Newton, I., Kavanagh, R., Olsen, J., & Taylor, I., CSIRO Publishing, Australia.

Kavanagh, R.P., Murray M. (1996) Home Range, Habitat and Behaviour of the Masked Owl Tyto novaehollandiae Near Newcastle, New South Wales Emu AUSTRAL ORNITHOLOGY 96(4) 250 – 257

Kavanagh, R.P. (1996) The Breeding Biology and Diet of the Masked Owl Tyto novaehollandiae Near Eden, New South Wales, Emu Vol 96, 158-165.

Loyn, R.H., McNabb, E.G., Volodina, L., Willig, R. (2002) Modelling distributions of large forest owls as conservation tool in forest management: A case study from Victoria, Southeastern Australia. In; Ecology and Conservation of Owls, pp242-254, Eds. Newton I., Kavanagh R., Olsen J., & Taylor I., CSIRO Publishing, Australia.

McNabb, E., McNabb, J., & Barker K. (2003) Post-nesting home range, habitat use and diet of a female Masked Owl Tyto novaehollandiae in Western Victoria. Corella, 2003, 27(4):109-117.

Norberg, A. (2002) Independent evolution of outer ear asymmetry among five owl lineages; morphology, function and selection, In; Ecology and Conservation of Owls, Eds. Newton I., Kavanagh R., Olsen J., & Taylor I., CSIRO Publishing, Australia.

Peake, L.E., Conole, L.E., Debus, S.J.S., McIntyre A. & Bramwell M. (1993) The Masked Owl Tyto novaehollandiae in Victoria. Australian Bird Watcher Vol. 15 (3) September 1993.

RFA (2000) West Victoria Regional Forest Agreement Consultation Paper January 2000, Joint Commonwealth and Victorian Regional Forest Agreemnt (RFA) Steering Committee.

Simpson, K. & Day, N. (1996) Field Guide to the birds of Australia, Simpson & Day, sixth edition, Penguin Books Australia Ltd.

Viridans (2005) Viridans Biological Databases.

VVB (2023) Visualising Victoria's Biodiversity map portal

More Information

Please contribute information regarding the Masked Owl in Victoria - observations, images or projects. Contact SWIFFT