Turquoise Parrot

Turquoise ParrotNeophema pulchella | |

|---|---|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Psittaciformes |

| Family: | Psittacidae |

| Status | |

| World: | Least Concern (IUCN 2025) |

| Australia: | Not Listed (EPBC Act 1999) |

| Victoria: | Vulnerable (FFG Threatened List 2025) |

| FFG: | Listed; no Action Statement |

Turquoise Parrot, The ‘Practical Parrot Action’ project.

Image: Chris Tzaros

The Turquoise Parrot Neophema pulchella is a beautifully coloured small sized parrot endemic to eastern Australia. It is a popular species with aviculturists but subject to strict licensing requirements and is fully protected in the wild.

Also known as the Turquoisine Parrot, Turquoise Neophema, Turquoise grass parrot , Beautiful Parrot, Turquisine grass parakeet, Beautiful parakeet, Red shouldered Parrot or Turk. It is one of six species in the genus Neophema, others being;

- Neophema chrysogaster Orange-bellied Parrot

- Neophema chrysostoma Blue-winged Parrot

- Neophema elegans Elegant Parrot

- Neophema petrophila Rock parrot

- Neophema splendida Scarlet Chested Parrot

The Turquoise Parrot is about 200-220mm long with a 320 mm wingspan. The male Turquoise Parrot is the most brightly coloured with highly distinctive plumage, bright green posterior and a turquoise-blue crown face. It has a chestnut-red patch on the upper-wing, with turquoise-blue shoulders, grading to deep at the flight-feathers. The upper margins of the breast have an orange tint, whilst generally a yellow abdomen is complemented by an orange centre. The female Turquoise Parrot and immature adults are somewhat duller in colour, have whitish lores, a green throat and breast and no chestnut-red on the shoulder or the upper-wing area (description from Higgins 1999; Pizzey and Knight 1997).

Distribution

The Turquoise Parrot range extends from east Gippsland in Victoria to New South Wales and into south-east Queensland. Its distribution is considered patchy and primarily determined by areas of suitable habitat.

Turquoise Parrot, Victorian distribution from all known records. Source: VBA 2018.

In Victoria, the Turquoise Parrot is mainly found in North East Victoria and east Gippsland. In east Gippsland it predominantly occurs around Mallacoota, but also north along Wingan River to Wangarabell, and near Bairnsdale and Bruthen; sometimes farther north along Snowy River, near Suggan Buggan. This species has also been recorded in north-east districts, between Echuca and Wodonga, and south to near Swanpool, south of Benalla (Traill 1988). Recent records from the Central District, in Glenburn and Yellingbo suggests several fragmented populations that may be re-established or drought-related within former range (Quin and Reid 1996).

The Turquoise Parrot is considered a local icon of the Glenrowan district which forms an important population across its range.

Ecology & Habitat

Turquoise Parrots are mainly found on the edges of forest and pasture or other grasslands (Morris 1980; Quin and Reid 1996; Jarman 1973) usually where there is permanent water. Preferred forests are grassy woodlands with mixed assemblage of native pine Callitris and a variety of Eucalyptus spp., such as Eucalyptus albens, Eucalyptus blakeleyi, Eucalyptus polyanthemos, Eucalyptus melliodora, Eucalyptus macrorhyncha, Eucalyptus populifolia or Eucalyptus sideroxylon (Morris 1980; Frith 1952; Quin 1990, Quin and Baker-Gabb 1993).

Individuals also inhabit savanna woodland and riparian woodlands and forests, including those on alluvial flats, such as stands of River Red Gums, Eucalyptus camaldulensis or Eucalyptus camphora (Frith 1952; Jarman 1973; Morris 1980; Campbell 1915; Quin and Reid 1996). The Turquoise Parrot may also occur in farmland, predominantly pasture, with remnant trees, living or dead, or tree stumps (Quin and Baker-Gabb 1993). It is seldom seen along roadsides and in orchards (Pizzey & Knight 1997).

In east Victoria and Gippsland Turquoise Parrot populations occur in lowland sclerophyll forest or coastal heathland (Traill 1988). These fragmented populations are suggested to be dependent on ectone between forest and heathland (Traill 1988; Emison et al. 1987).

Dead trees comprise an important part of habitat and are preferred for look out posts and nesting.

Movement

This species rarely forms large flocks and a commonly observed in pairs or small parties of 6-8 individuals (Higgins 1999). Larger flocks of 20-30 birds may occur from autumn and through winter after the breeding season.

Feeding

The Turquoise parrot is predominantly a ground feeder, foraging usually on seeding grasses or weeds, herbaceous plants and shrubs, generally growing beneath trees (Frith 1952; Jarman 1973; Morris 1980; Quin 1990; Higgins 1999). Diet consists of seeds from beared heath, Leucopogon microphyllus, barley grass Hordeum murinum, wild mustard Sisymbrium spp., wallaby grass Danthonia semiannualaris, stinging nettle Urtica urens and saffron thistle Carthamus lanatus (Crome and Shields, 1992). Flowers, nectar, leaves, fruits and scale may also be consumed by the Turquoise Parrot (Quin and Baker-Gabb 1993).

Diet consists of seeds from beared heath, Leucopogon microphyllus, barley grass Hordeum murinum, wild mustard Sisymbrium spp., wallaby grass Danthonia semiannualaris, stinging nettle Urtica urens and saffron thistle Carthamus lanatus (Crome and Shields, 1992).

In the Warby Ranges-Chesney Hills district low groundcover plants such as Common Raspwort, Black-anther Flax-lily and Native Geranium. Fruits from small shrubs such as Bush-peas, Guinea-flower, Daphne Heath and Fringe-myrtle are also consumed. Some weeds such a Capeweed and Blue Heliotrope are important food plants seasonally.

Nesting

The Turquoise Parrot main breeding season is from August to January (August to November in North-east Victoria). Turquoise Parrots nest in hollow-bearing trees, either dead or alive also, in hollows in tree-stumps (dead, ringbarked, burnt or coppicing), fallen logs and fence posts (Chaffer and Miller 1946; Barker 1953; Jarman 1973; Quin 1990). Preferred breeding habitat is an ecotone between farmland and forests. Open grassy forests and woodlands; in gullies and on low slopes of foothills that are moist and seasonally waterlogged are used; occasionally they breed on ridges (Quin 1990; Quin and Baker-Gabb 1993).

Hollows tend to be small diameter but deep and located 1.5-3 m above ground. The use of artificial and natural nest boxes has been successful when positioned in the right place.

A detailed study in North-east Victoria, found that most breeding occurred in forests dominated by either Blakeley’s Red Gum or Warby Swamp Gum only, or in mixed assemblages of Blakeley’s Red Gum, Red Box and White Box, Mugga Ironbark and Red Stringy Bark, or Red Box and Red Stringy Bark (Quin 1990; Quin and Baker-Gabb 1993). Turquoise Parrots also breed in partly cleared land, cleared pasture with stumps remaining, or in remnant vegetation along roadsides (Quin 1990; Quin and Baker-Gabb 1993). Most nesting sites in north-east Victoria occur within 100m of cleared land, and breeding in either forests or pastures rarely occurs >1 km from the edge of forest (Quin 1990; Quin and Baker-Gabb 1993).

A standard clutch usually consists of 2-5 eggs, although up to 6 eggs has been recorded. Some breeding pairs may also raise a second brood during summer months (Higgins 1999). Both parents feed the young which remain in the hollow for about 4 weeks after the 18 day incubation period. The female only leaves during incubation of the clutch to drink, during which time the male accompanies her (Higgins 1999; Quin 1990).

Turquoise Parrot chicks in artificial nest hollow. The ‘Practical Parrot Action’ project. Image: C. Tzaros

Male feeding young in artificial nest box. The ‘Practical Parrot Action’ project. Image: C. Tzaros

Population Status

In the early part of the century the Turquoise Parrot suffered a severe decline in numbers, with certain observers even regarding it as extinct (Campbell 1915). Populations recovered somewhat from the 1930s onward (Chaffer and Miller 1946; Frith 1952; Forshaw 1981; Blakers et al. 1984) and in Victoria populations in the north-east of the state are still increasing in distribution and numbers (Quin 1990). However, the Turquoise Parrot is still considered as restricted and rare in Victoria (Forshaw 1981; Anon. 1987).

The Turquoise Parrot was listed as Vulnerable on the FFG Threatened List - June 2023.

Threats

The Turquoise Parrot is threatened by:

- Loss of habitat due to clearing of private land and conversion to agricultural pasture, burning and intensive logging.

- Destruction and removal of remnant sites that contain dead or alive hollows that may be used for nesting. Silviculture practices have also contributed to the scarcity of hollow-bearing trees.

- Inappropriate fire regimes that destroy feeding and nesting resources.

- Individuals commonly feed on the ground and nest in hollows close to the ground, and consequently suffer from high levels of predation from introduced carnivores (e.g. European red fox, Vulpes vulpes, and cats).

- Its small isolated populations are particularly susceptible to sudden catastrophes such as disease and natural disasters (e.g. fires).

- Illegal trapping of birds and collection of eggs, which also contributed to the destruction of tree hollows.

- Competition from non-endemic seed-eating species; and

- loss of genetic variation due to is small isolated population sizes.

Conservation & Management

The conservation status of Turquoise Parrot was re-assessed from Near Threatened in 2013 (DSE 2013) to Least Concern in 2020 as part of the Conservation Status Assessment Project – Victoria (DELWP 2020).

Long term conservation efforts are aimed at establishing a healthy, self-sustaining wild population requiring no input of captive-bred stock or other management effort.

Suggested management priorities

- Co-operation with private landholders to locate new sites and maintain existing sites, and from this negotiate, develop and implement conservation management agreements for high priority sites;

- Identify sites where the species is commonly observed and target to incentives and ecosystem management (protection of hollow bearing trees);

- Implement control plans for feral species, including weeds, foxes, cats and rabbits for target sites to decrease predation and competition and increase available resources;

- Develop nest box projects with landholders to increase nesting opportunities.

- Protection of nesting hollows: Identify and isolate exclusion zones for all known Turquoise Parrot populations in east Gippsland, southern central district (Yarra Ranges) and east northern sites. Ensure any additional suitable nesting hollows are protected from logging, silviculture and agricultural grazing; special attention should be given to these sites that exist on the ectone between remnant woodland and pasture.

Projects & Partnerships

Turquoise Parrot nest box project - Goulburn Broken CMA

The ‘Practical Parrot Action’ project

This project is managed by the Goulburn Broken CMA, through the Broken Boosey Conservation Management Network. The project focuses on the Turquoise Parrot in the Warby Ranges-Chesney Hills district, with an emphasis on understanding how and why it uses the sites where it occurs through regular monitoring, and working directly with farmers, landholders and schools to protect and restore key areas of habitat, especially nesting sites, on private land.

The project started in 2014 with a Threatened Species Initiative grant from DELWP for two years. During this time a baseline study was carried out, 150 nest boxes were built and located on private land, with some monitoring. The project involves significant landholder engagement, community talks and presentations, field days, media including ABC radio, nest box building workshops and a booklet ‘Turquoise Country’ by Chris Tzaros.

On-ground activities

On-ground actions involving landholder participation includes habitat fencing, revegetation, nest box placement and bird monitoring. Community education through Field days and school education events is also an important part of the project.

Community involvement

The project has realised a tremendous amount of community interest and support for conservation of the Turquoise Parrot. The project launch in May 2014 was attended by 94 people, workshops attract a similar level of attendance. A field day had 105 attendees and other events have drawn a healthy attendance.

Landholders who wish to be involved When nest boxes are set up on private property, we encourage the landholder to get involved, as we need them to monitor and be responsible for the nest boxes.

Progress

Between 2014 and 2018 there has been six turquoise parrot-focused projects which the Broken Boosey Conservation Management Network has undertaken in the Warby Ranges area, the Chesney Vale Hills area, Everton/Chiltern area and Warby Ranges-Killawarra regions in North-east Victoria.

The total number of built nest boxes installed in the area will be 552 by the time this latest project is completed in 2020. Plus, a further 150+ ‘nest boxes’ that have been made from hollow logs that were salvaged from the 2014 Wunghnu Complex bushfires ‘clean up’.

Chris Tzaros carries out monitoring at a selection of sample sites and has recorded around 20 nest boxes which are known to have fledged chicks.

Natural hollow logs salvaged from bushfire ‘clean up’ area. A square timber is attached at end on the log. The hollow log needs to be the right dimensions to be suitable for Turquoise Parrots to use. These types of hollows can be attached to fence posts or used as stand-alone nest logs. Source: GBCMA

Recommended nest box construction and placement

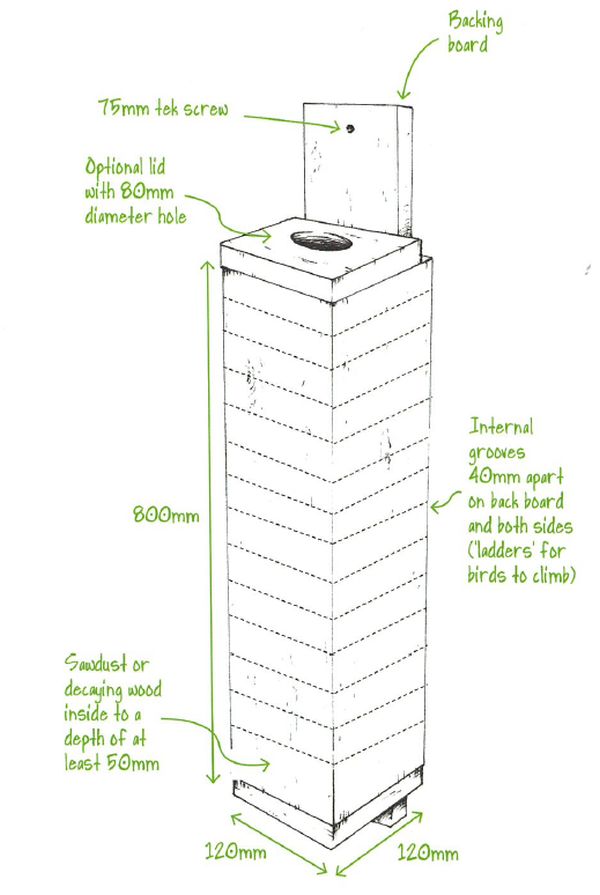

Turquoise Parrot nest box. The typical dimensions are 120mm x 120mm x 800 mm with an 80 mm hole at the top. Internal groves 40 cm apart. Around 10cm of dry sawdust-y matter is placed in the bottom of the box. Source: GBCMA Nest Box Plan.

Site selection

In North East Victoria, placement needs to be in the higher country preferably in known feeding or nesting habitat such as mixed Blakely’s Red Gum and Red Stringybark woodlands.

Boxes should be within 100 m of forest or if positioned within the forest 100 m from open land. There needs to be adequate levels of shade and within 250 m of water with gently sloping banks.

It has been found the Turquoise Parrot moves about a lot looking for nesting sites. Therefore, boxes need to be located across as much suitable territory as possible.

Attachment

Nest boxes can be attached to stumps, low on dead trees, live trees and ‘stand-alone’ using parallel star pickets can be used. For attachment to live trees a large screw through the backing board is recommended. It has been found the ‘stand-alone’ method may reduce predation from climbing species.

Monitoring

It is important to monitor nest boxes prior to and during the breeding season (Autumn and Spring) to ensure they are free from unwanted pests and have enough saw dust/shavings etc. at the base for nesting. If nesting detected avoid disturbance. Reports successful nesting to project co-ordinator. Boxes need to be cleaned out at the end of the season and made ready for the next breeding season.

Contacts

Janice Mentiplay-Smith, Goulburn Broken Catchment Management Authority, Conservation Management Network Coordinator.

Chris Tzaros, Bushland Birds and Beyond.

References & Links

AFD (2018) Australian Faunal Directory, Australian Government, Department of Environment & Energy. Turquoise Parrot.

Anonymous. (1987) Conservation in Victoria: 1. Plants and Animals at Risk. Department of Conservation, Forests and Lands, Melbourne.

Barker, W. (1953) Emu 13: 62.

Blakers, M., Davies, S.J.J.F. and Reilly, P.N. (1984) The Atlas of Australian Birds, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne.

Campbell, A.J. (1915) ‘The Turquoise Parrot’. Emu 14: 167.

Chaffer, N. and Miller, G. (1946) ‘The Turquoise Parrot near Sydney’. Emu 46: 161-167.

Chilcott, C., Reid, N.C.H. and King, K. (1999) ‘Impact of trees on the diversity of pasture species and soil biota in grazed landscapes on the Northern Tablelands, NSW’, in P. Hale and D. Lamb (eds), Conservation Outside Nature Reserves, pp. 378-386. Centre for Conservation Biology, Brisbane.

Crome, F. and Shields, J. (1992) Parrots and Pigeons of Australia. Angus and Robertson, Sydney, Australia.

DELWP (2020) Provisional re-assessments of taxa as part of the Conservation Status Assessment Project – Victoria 2020, Department of Environment Land Water and Planning, Victoria. Conservation Status Assessment Project – Victoria

DSE (2013) Advisory List of Threatened Vertebrate Fauna-2013 on DELWP Advisory Lists 2018.

Emison, W.B., Beardsell, C.M., Norman, F.I. and Loyn, R.H. (1987) Atlas of Victorian Birds, Dept. Conservation, Forests and Lands and the Royal Australian Ornithologists Union, Melbourne.

FFG Threatened List (2025) Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988 - Threatened List - March 2025 Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action (DEECA), Victoria.

Forshaw, J.M. (1981) Australian Parrots, 2nd Edn., Landsdowne, Melbourne.

Frith, H.J. (1952) ‘A record of the Turquoise Parrakeet’. Emu 52: 99-101.

GBCMA (2018) Goulburn Broken Catchment Management Authority, The ‘Practical Parrot Action’ project, Janice Mentiplay-Smith.

Higgins, P.J. (1999) Handbook of Australian, New Zealand and Antarctic Birds Volume 4. Oxford University Press, Melbourne, Australia.

IUCN (2025) BirdLife International. 2024. Neophema pulchella. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2024: https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2024-2.RLTS.T22685209A254010000.en. Accessed on 28 April 2025.

Jarman, H. (1973) The Turquoise Parrot. Aust. Bird Watcher 4:239-250.

Lumsden, L.F. and Bennett, A.F. ( 2005) ‘Scattered trees in rural landscapes: foraging habitat for insectivorous bats in south-eastern Australia’, Biological Conservation. 122: 205-222.

McIntyre, S. (2002) ‘Trees’, in S. McIntyre, J.G. McIvor and K.M. Heads (eds), Managing and Conserving Grassy Woodlands, pp. 79-110. CSIRO Publishing, Collingwood, Australia.

McIvor, J.G. and McIntyre, S. (2002) ‘Understanding grassy woodland ecosystems’, in S. McIntyre, J.G. McIvor and K.M. Heards (eds), Managing and Conserving Grassy Woodland, pp. 1-23. CSIRO Publishing, Collingwood, Australia.

Menkhorst, P. And Middleton, D. (1991) Helmeted Honeyeater Recovery Plan 1989-1993, Dept. Conservation and Environment, Melbourne.

Morris, A.K. (1980) The status and distribution of the Turquoise Parrot in New South Wales. Australian Birds 14:57-67.

Pizzey, G. And Knight, F. (1997) Field Guide to the Birds of Australia. Angus and Robertson, Sydney.

Quin, B.R. (1990) Conservation and Status of the Turquoise Parrot (Neophema pulchella, Platycercidae) in Chiltern State Park and Adjacent Areas, M.Sc. thesis, La Trobe university, Melbourne.

Quin, B.R. and Baker-Gabb, D.G. (1993) Conservation and Management of the Turquoise Parrot in North-east Victoria, Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research Technical Report Series 125.

Quin, B.R. and Reid, A.J. (1996) The Turquoise Parrot Neophema pulchella in the Yea and Yarra River Valleys, Central Southern Victoria. Australian Bird Watcher 16: 250-254.

SFNSW 1994. Appendix 1 in Proposed Forestry Operations in Eden Management Area. Fauna Impact Statement.

Shaw, G. (1792) The Naturalists’ Miscellany, Volume 3, plate 96.

Traill, B.J. (1988) ‘The Turquoise Parrot in East Gippsland’. Australian Bird Watcher 12:267-296.

VBA (2018) Victorian Biodiversity Atlas, Department of Environment, Land, Water & Planning, Victoria.

Please contribute information regarding Turquoise Parrot in Victoria - observations, images or projects. Contact SWIFFT